Marco Polo's odyssey spawned one of the world's first best sellers

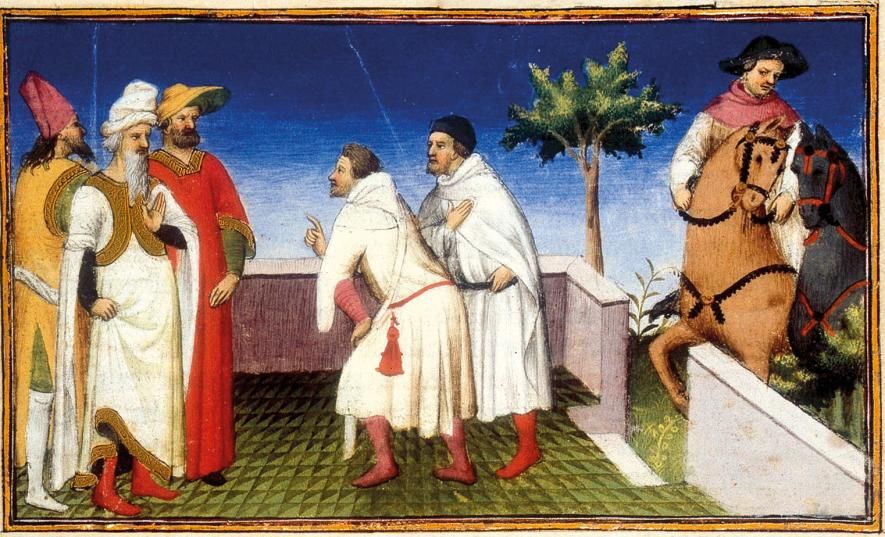

The world-famous explorer Marco Polo is credited with many things, but perhaps the greatest is compiling one of the world’s first best-selling travelogues. Published around 1300, the book chronicles his experiences during a 24-year odyssey from Venice to Asia and back again.

Polo did not write down his adventures himself. Shortly after his return to Venice in 1295, Polo was imprisoned by the Genoese, enemies of the Venetians, when he met a fellow prisoner, a writer from Pisa named Rusticiano. Polo told his stories to his new friend, who wrote them down and published them in a medieval language known as Franco-Italian. (See also: Photo Gallery: The adventures of Marco Polo.)

Although the original manuscript is lost, more than 100 illuminated copies have survived from the Middle Ages. Many of these are of great beauty, but there are significant discrepancies among them. The work came to be known as Il Milione, perhaps based on a well-known nickname of Polo’s. In the English-speaking world, the book is often known as the Travels of Marco Polo.

The Bodleian Library in Oxford, England, holds one of the earliest versions, dating from about 1400. Gorgeously rendered, the Bodleian copy contains what many scholars consider to be an authoritative text. It tells the story, beginning in 1271, of an odyssey undertaken by a trio of Venetians, who traveled through extraordinary lands and into places where few Christians had ever been, all the way to the court of the Mongolian emperor, Kublai Khan. (See also: Who were the Mongols?)

The names of the places they traveled—Hormuz, Balkh, and Kashgar—became for Europeans indelible parts of a new mental map of the world. Although fantastic legends and rumors from such far-off places had filtered through to Europe on the numerous east-west trading routes of the Silk Road, Polo’s eye brought them alive in a new way. He wrote of fabulous things, but also of everyday matters relating to commerce. (See also: Silk for horses: History of the Silk Road.)

His book became a best seller, spreading throughout the Italian Peninsula in a matter of months—a remarkable feat in an age before Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press around 1439. Polo’s book reawakened Europe to the possibilities of international trade and expansion, and became a text that heavily influenced the age of discovery that dawned in Europe two centuries later.

MAPPING THE MODERN WORLS

Using information given by Marco Polo in his Travels, Venetian monk Fra Mauro created this map of the world around 1450, more than a century after Marco Polo’s works had been published. Now held in the Marciana National Library in Venice, it shows a world whose contours were growing more precise and detailed than Europeans had ever known before

Mongolian rule

Marco Polo was born in 1254, at a time when Europe was looking not westward to the Atlantic, but eastward with fascination and trepidation. By this time, Mongol hordes had reached Hungary. By the time of the Polos’ great journey 17 years later, the Mongol empire had reached its maximum. Its northwest component, the Khanate of the Golden Horde, stretched as far west as the Danube River in central Europe. The easternmost part of the empire stretched to Asian shores of the Pacific.

The largest contiguous land empire the world had ever known emerged from a group of warring tribes. In 1206 a single leader, Temüjin, was elected Genghis Khan (meaning “Universal Ruler”) after he won a series of victories over his rivals. Temüjin enjoyed unprecedented control over what is now Mongolia. With the accession of this fearsome leader, the federation of tribes began expanding their strongholds beyond the Mongolian steppe.

They first turned east, to the kingdoms of north and western China, eventually reaching Beijing, which fell to them in 1215. From then on, state after state across China and Central Asia was absorbed into the expanding Mongol empire. The Mongols even raided lands in southern Russia. (See also: Do walls work? The Great Wall of China.)

At the time of Genghis’s death in 1227, Mongol horsemen patrolled the shores of both the Caspian and China seas; they were in Siberia, Tibet, and the central Chinese plains. They were also present along the Silk Road, a great artery of trade, commerce, and information.

VENETIAN SEND-OFF

A 15th-century illustration from Marco Polo’s Travels, held by the Bodleian Library, Oxford, shows the Polos’ departure from Venice. St. Mark’s Basilica with its four bronze horses is recognizable (left) and alongside it is the Doge’s Palace. In front are the columns of St. Theodore and St. Mark, topped by a winged lion. The inclusion of exotic animals (lower left) hints at the wondrous thing to come on their epic voyage.

From 1236, the Mongols began to look farther west and turned their attention to Europe. In a series of shatteringly aggressive campaigns, they stormed through what is now Ukraine and Poland, taking Kiev in 1240 and sacking Krakow the following year. A successful invasion of Hungary opened the way for Mongol armies to enter Austria, raiding south of Vienna. Here they were at last turned back.

Word of the speed of Mongolian conquests and the apparent invincibility of their horse- men spread throughout Europe. When Polo set out on his journey, there would still have been many survivors of the Mongol invasions. Even so, fear of Genghis Khan was mixed with curiosity about his people. Some enterprising Europeans even had hunches that money could be made through more contact with the Mongolians.

A family of travelers

Europe’s great seafaring republic, Venice, maintained a vast network of trading contacts throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East. It was poised to begin expanding its trade network eastward. Venice was home to merchants with an in-depth knowledge of the East and among the best placed to chase riches. Throughout the medieval period, they traveled the routes east to Trebizond, the gateway to the Silk Road (located in today’s Trabzon in modern Turkey). Goods moved between China and Europe along this route.

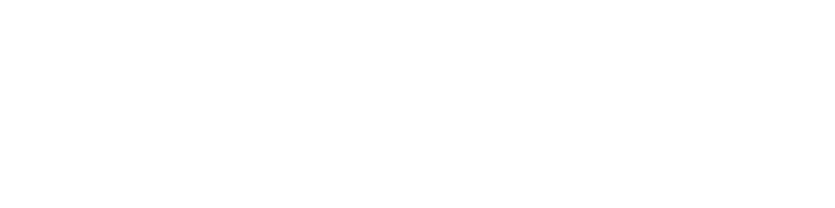

Marco Polo came from a family of merchants. When he was a small child, his father Niccolò and uncle Maffeo were already amassing some remarkable travel experiences. The shrewd traders had left Venice in 1261 to forge new relationships in the East. The pair had met the Mongolian khan as part of this first epic journey.

One of the Polos’ commercial bases was Constantinople, where their brother, Marco senior, worked. Their agents operated up the Volga River into Bukhara. It was there in modern Uzbekistan that Niccolò and Maffeo had pulled off a major diplomatic feat: They met members of Kublai Khan’s government and arranged an expedition to his court in Shangdu (in Inner Mongolia in modern China).

The Polos were not the first Westerners to penetrate the vast Mongolian domains, nor even to meet the ruling khan of the day. One pioneer was the Franciscan friar Giovanni da Pian del Carpini, who in 1246, on behalf of Pope Innocent IV, arrived at the court of Güyük (the third Great Khan) after a lengthy and arduous trip by land. Equally significant was the experience of Willem van Ruysbroeck, a Flemish friar, who in 1254 made it to Karakorum, the capital of Möngke (the fourth Great Khan), as an emissary of Louis IX, king of France. Unlike Marco Polo’s account, however, the reports of the roving friars did not find a wide public, and did not shape the European imagination to such an extent.

Their meeting with Kublai Khan was one of history’s great encounters between East and West. In the khan, the two Venetians found a man whose curiosity about the West matched theirs about the East. The relationship they built with the Mongols made the brothers pioneering intermediaries, a conduit through which knowledge of Europe and China could travel in both directions.

Intrigued by what the brothers told him about Europe (and especially about Christianity), the khan asked them to return to Europe and petition the pope to send learned men to teach the Mongols about Christianity. The Polos’ return home was long and arduous. Things became more complicated when they reached Acre (in modern Israel) and learned that Pope Clement had died, and there was no elected successor.

The brothers continued back to Venice, where they would await a new pope and plan their return to the court of Kublai Khan. This time, they would bring Niccolò’s son, Marco. A boy when the father had last seen him 10 years ago, he was now a young man at 17 years old.

To the court of Khan

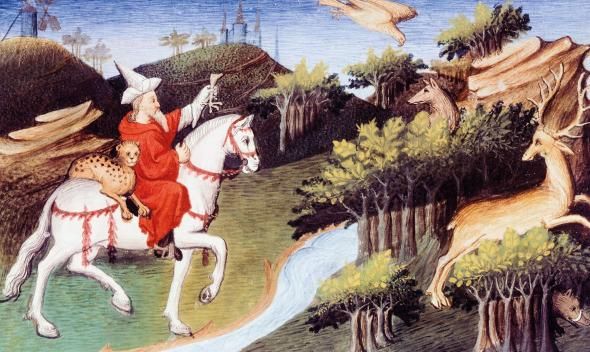

In 1271 father, son, and uncle left Venice and sailed to Acre. From there they swung northeast, taking a route that stretched overland through eastern Anatolia and Armenia to Tabriz, in present-day Azerbaijan. Next they headed south through the Iranian highlands, skirting Baghdad, aiming for the Strait of Hormuz, from where they intended to take a ship across the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean all the way to China.

Inspection of the available boats, however, alarmed them. They were, Polo would later describe in his Travels, “wretched affairs . . . only stitched together with twine made from the husk of the Indian nut.” In the end, they decided to make the journey by land.

Marco Polo was always interested in the goods a region produced, how it connected with Europe, and how it could connect in the future. Tabriz, for example, “is excellently situated so the goods brought to here come from many regions. Latin merchants . . . go there to buy the goods that come from foreign lands.” The Persians, he observes, produce “the best and handsomest carpets in the world.” In Baghdad: “a great river [the Tigris] runs through the midst of it by means of which merchants transport their goods to and from the Sea of India.” These details were important for future trade between Venice and East Asia.

Despite his report on the city, it is unlikely Marco visited Baghdad, as the city had been laid to waste by the Mongols slightly more than a decade before. Neither are historians sure if Marco Polo visited Mosul, although he certainly gathered a lot of information about the city’s textile trade. .

Three and a half years traveling through Central Asia brought hardship to the family. Polo later recalled suffering attacks by bandits and severe illness while passing through Afghanistan. After surviving it all, the Polos eventually made their royal rendezvous. Marco Polo, then age 21, became one of a select few to be received by a khan—in this case, the fifth Great Khan, Kublai—at his summer palace at Shangdu.

By his own account, Marco was popular with Kublai Khan himself, and could speak the khan’s tongue. The Polos spent nearly 17 years in his employ in China and its neighboring lands. Marco was sent on many journeys around China, and farther afield to Pagan in modern-day Burma, and to the old Mongolian capital at Karakorum far to the north.

When the time came to return to Europe, the Polos’ sea voyage home was another epic journey, taking them through the South China Sea, Vietnam, Malaysia, Sumatra, and Sri Lanka. The Polos rounded the southernmost tip of India and sailed north up the western coast until they disembarked and continued overland to Afghanistan. From here, they slogged through Persia and the Middle East, on to Constantinople, from where they finally sailed for Venice. After an odyssey of 24 years, they arrived home in 1295.

Birth of a best seller

Marco Polo’s account of his journey became a best seller partly because of its new insights into a faraway part of the world: Although travelers’ tales from the lands of the Silk Road had been distributed before, the wealth of information Marco Polo provided on China and its surrounding lands was unprecedented in its time.

The Travels became famous, even notorious, for their tall tales. One such story is an account of plants that produced pasta (this latter, however, is almost certainly a misinterpretation; Polo surely knew pasta did not grow on trees!). Nevertheless, the book also spins tales about hungry cannibals and giant unicorns (some believe they were rhinos) who lived on Sumatra. On an island called Angaman (believed to be the Andaman Islands), it describes people with heads like dogs. (See also: Marco Polo and the 'Assassins' of Alamut.)

Even when the stories are not fabulous, their provenance is often hazy. The only source of information for the Polos’ route is Marco’s account, and it is not always easy to distinguish between what the family actually saw with their own eyes and what stories they were told by others. With its mix of hearsay and occasionally disjointed, rambling style, episodes of Polo’s account have been regarded as a fabrication by some commentators. Polo described a place called Cipangu with a palace so richly endowed that its floors were lined with gold “more than two fingers thick.” Most historians agree that Cipangu is Japan but that Polo never went there. Much of this account is believed to be secondhand, at best. Even so, most historians consider that Polo’s account of his travels in China is based on authentic, lived experience.

The work was also attractive to readers because of its commercial emphasis. Not only did it offer readers strange and fantastic details about faraway places, it also presented practical information of use to merchants interested in international trade. Polo describes China as a “merchants’ paradise” and includes down-to-earth data on the intricacies of Chinese law.

Polo’s eagerness to record the goods being produced and how they could be transported, caught the mood of the times. Information from the Travels was useful in improving maps of East Asia, which fed trade relations. Marco Polo’s work also inspired travelers to retrace his steps to China, bringing back yet more information on these lands. This knowledge fueled a growing curiosity about the world as Europe moved into the Renaissance and the age of discovery toward the end of the 1400s. Better navigation enabled eastward as well as westward trade in that feverish period of exploration.

In 1557 the rulers of China’s Ming dynasty allowed Portugal to create a permanent settlement at Macau, and it was from this trading post that the Italian Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci began his attempt to evangelize across China. His profound knowledge of the country enabled him, and fellow Jesuits, to explain Chinese beliefs and customs to the West, continuing the cultural bridge that Marco Polo, his father, and his uncle, had begun building two centuries before.